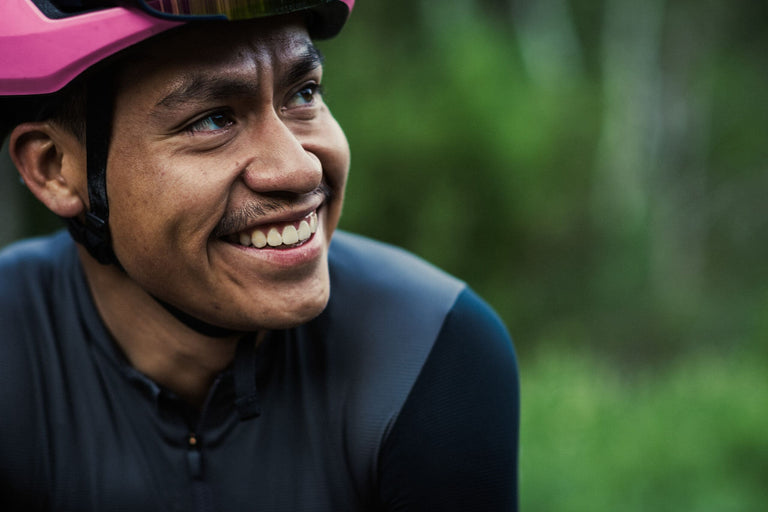

Born in Guatemala City, DACA recipient Alvin Garcia migrated with his family to the United States in the late ‘90s. Now residing in Salt Lake City, Alvin is a routesetter at The Front Climbing Club and spends his free time climbing, running and cycling … usually with a few friends by his side.

“Fuel for Life: Alvin Garcia,” a film by Tommy Chandler, explores community as a foundation in Alvin’s life, and in all of his pursuits.

We went behind the scenes with Alvin and Tommy to uncover more information about Alvin, what being a DACA recipient means, and the filming process.

Alvin, when we first approached you with this project, you were hesitant to partake. Can you expand on those initial thoughts?

When you first came to me with the project, I hesitated because my story is so common to so many. But through the process of filming and doing the interview, and sitting down and thinking about how I can connect with others and how I can potentially inspire people who have been through the same, or have similar circumstances, I’ve started to discover how important it is to be human, and to have simple human connections.

Tommy, describe your relationship with Alvin.

Alvin and I first met while working at The Front Climbing Club and Vertical Solutions. Alvin is an outgoing person with a good attitude, so it was easy to initially connect. I never had a chance to get to know him super well, but I always enjoyed it when we crossed paths and got to work together.

As Alvin was getting into cycling, I was able to share with him that I used to be more involved in that world, so it was cool to see him get psyched on bikes and to share my experiences with him. But it wasn’t until this project that I really was able to dig in and learn more about his life, how he arrived in the United States, and what his situation is with DACA.

Alvin, what was it like working with Tommy to share a story that is personal to you? Can you describe the process of piecing it together?

It played out perfectly because knowing Tommy from previous experiences allowed me to trust him and build a deeper connection easily. I think if I worked with someone else, I would’ve had a bigger jump to make. My story can be sensitive, so it made me comfortable to have Tommy on this project.

Tommy, how did you decide what questions to ask, and what specifically to focus this film on?

Alvin and I had a few pre-production conversations to uncover what the best talking points would be, like how certain moments have shaped his experiences of arriving in the United States, and in his life now.

Over time, I’ve realized the best way to capture a story well is to immerse yourself in it. This is obviously difficult with Alvin’s situation, but I did my best to learn as much as I could about him, which helped visualize the narrative and form questions to drive that story.

You decided to film this video as interview-style. Why this approach?

It was really important for Alvin to tell his story, and to see his face and listen to him talk. This helps the viewer connect with him in that way. I think there’s a lot of power in hearing someone speak directly. It’s an effective way to tell someone’s story.

What was the process like of creating this film with Alvin?

We had a lot of initial conversations simply around whether or not it was safe to tell this story, considering Alvin’s DACA status. He decided it was more important to make people aware of this type of situation that others in the country are in, rather than to keep it hush-hush. Alvin realized it was important to let people know what is happening, and that this is a situation that needs to be discussed, so it can be improved.

Why did you shoot where you did, and include the other people, too?

I wanted to use Alvin’s favorite sports as a frame of reference for his position in life. The way that sports have contributed to his community connections was important to illustrate. And the same by showing his mom, who has had a big influence on him.

For a little while, Alvin’s mom was away in Guatemala. When she got back, his family had a cookout with his grandma and friends. And then his friend hosted a little backyard barbecue, so it made sense to show both the family and friends that have contributed to the person Alvin has become.

In the film, Alvin talks a bit about what his path is, and how the uncertainty of not knowing whether or not he’ll get deported affects his ability to make long-term plans. So, it was important to show how hard of a worker he is in a space that has taken care of him, which is why we shot at The Front, too.

Describe how your own artistic approach influenced the storytelling of this film.

I wanted to balance a documentary and cinematic style. Some portion of this film has Alvin telling stories about what has happened in his past, and others speak to more current events. From a documentary standpoint, it was important to show old photos, and Alvin with his friends and family. In terms of cinematic, it was important to show high-quality imagery of his current passions, like cycling and soccer.

Alvin, take us through a timeline of how and when you arrived in the United States.

I was born in Guatemala and traveled through Mexico with my family to get to America. We crossed into American territory just south of Tucson, AZ, and lived there for a year or two. An uncle of ours was living in Park City at the time, so we moved there when I was in second grade. Once we were able to establish ourselves financially, my mom bought a house in Salt Lake. We have been here ever since.

What about Salt Lake gives you a sense of home?

At first, Salt Lake kept me here because of the little bit of resources. As an immigrant, we don’t have a lot of outside financial support – the biggest thing is family. I still live with my family and we all support each other in that way. But Salt Lake took on a bigger role once I got out of school because I was exposed to the outdoors, and I don’t think I would be a part of any great community right now if it wasn’t for sports. Soccer turned into boxing, boxing turned into climbing, climbing turned into cycling and a bigger community. And now, my job.

What is the hardest part of being an immigrant under DACA?

I look at DACA as a subscription. Every case is a little different – some people have to pay every few years or one year, but you have to renew this subscription to the government.

Unfortunately, the DACA program doesn’t protect us as a path to citizenship, so it feels like I never know when the program will end, or if I will be able to pay for it each time. This brings a lot of uncertainty. One day I could be living here, then the next I could wake up in Guatemala.

Watch the full film!

Was it ever difficult for you to find or create a community?

The language barrier was not major for me just because I was young and picked up English quickly. But it was and has always been through sport that I’ve been able to connect with others. I know that if everything were to fail, I could go and connect in a sport, and find help or friends through that.

How have different sports that you’re a part of helped to shape your community, past and present?

I played soccer in college and my goal was to make it out as a pro. Once I realized that wouldn’t happen, and that I wasn’t able to afford school, I came back to Salt Lake and discovered boxing. I had to pivot after having surgery from that sport, which is when a friend invited me to go climbing. That sport has now become my income through The Front, and the biggest foundation of my community. The climbing community allowed me to feel welcome, and once someone feels welcome and valued, they also have the ability to process and develop as an individual. Feeling whole and appreciated allowed me to look for other ways to connect with more people.

Then, at the climbing gym, a friend presented cycling as a hobby. At the beginning, it was a way to decompress after work. But now I’ve connected with so many in that sport, and it has given me another community. I love being able to bring both my climbing and cycling friends together.

Tell us more about your family’s influence on you.

The building block of my life and my main example for living has always been my mom. In the video, I talk about traveling from Guatemala and the decisions she had to make to do that. When we were in Park City, we cleaned houses with her as little kids. At times we lived out of our car, but she would work three jobs and feed us and just lower her head and provide her kids with the essentials.

What is it like knowing that, while you’re building and nurturing your community, your DACA status could change?

For context, my mom fought deportation for 13 years. When they finally granted her citizenship, they did not process her kids in the same way. We were left in the air with no clear way to do the same.

The “what if’s” can cause a lot of stress and fear, especially in young people, especially for someone trying to figure out their life. But I’ve tried to take on a different perspective: The fact that DACA is basically a subscription that can expire at any time has pushed me to appreciate what I do have in my community. This fact has made me more present, and I try to appreciate everyone I come across because I think how shitty it would be to wake up tomorrow and to have every friend or sport currently in my life taken away.

You tend to maintain a positive attitude, even through injuries and other uncertainties. How does this optimistic perspective affect your daily life and the people you meet?

A lot of uncertainty will leave you crippled at times, sometimes it leaves you suicidal or in dark places. But I get my power and my breath when friends and family allow me to be myself, and are there for me, which in turn allows me to maintain a positive attitude. I try to look at things more positively because I think those little changes in views push me to believe that we have more value in this country and in this life. We should believe more in ourselves.

What is the main takeaway you’d love for people to walk away with after watching your film?

I think the only goal I have with telling my story is to make everybody feel a little more welcomed. There are people around us that relate to the things I have gone through in life. There are others looking for a community, too.

Are there any last comments either of you would like to make?

Tommy:

I’m super grateful to Alvin for putting himself out there and being willing to do this project, and to his family for inviting me into their lives and home.

I hope people appreciate Alvin’s story and that it helps people understand more clearly what is going on with immigration in America. Not from a political standpoint, but more so from the fact that we are all humans with our own stories. It’s easy to form opinions when you don’t know someone’s motivations or what they’ve been through. That’s the core of this story: when you spend time doing any activity with someone, all the other disagreements or opinions fall away, and you can just connect with a person in a real way.

Alvin:

I would simply like to appreciate and thank everyone who I’ve crossed paths with in my life. I’ve been blessed with amazing people who have been so impactful. Thank you to everyone who has supported me throughout my life.